What It’s Like To Face The LGBT Inquisition

On the night of October 3, 2014, I was still recovering from a successful launch of a scholarly institute devoted to advancing children’s rights around the globe. The event went up without a hitch in Simi Valley. One hundred and twenty of my students had produced 80 research exhibitsdrawing from antique literature to give context to a discussion about the history of “family.”

In my life as a scholar, I had struggled to arrive at a moment such as this. Scholars come from somewhere. Growing up the awkward Latino child of lesbians in the uncharitable milieu of 1970s Buffalo, I overcame racism and sexual prejudice all my life with literary craft, reading and writing, witticisms, and intellectual adventures. The bigots who scrawled “SPIC” on the chalkboard when I was at school and threw homophobic slurs at me could not trespass on my sacred ground: Nihil humanum mihi alienum puto, wrote the great poet Terence. Nothing that is human is foreign to me. The world, with its splendiferous cultures and deliciously capricious languages, belonged to me, as long as I was reading and writing.

People with literary inclinations are always whimsical, experimental, even a little reckless. Long ago, the heroes whom I chronicled in my monograph, The Colorful Conservative: American Conversations with the Ancients from Wheatley to Whitman, engaged in all the dangerous flirtation with new ideas that I would find irresistible. Phillis Wheatley rearranged the ideas of Horace; Thoreau subverted Homer; Whitman toyed with Virgil; William Wells Brown reinvented Cato. For most of my life I have aspired to be like these independent thinkers.

Can’t We Ask Questions and Explore Ideas?

But it was really only at the October 3 event that my life as a scholar came full circle. Tenured, well-published, and connected to international allies who could give me a serious chance at disseminating my commitment to the rights of children, I felt I could address a serious gap in research—the question of whether gay parenting as it has evolved is ethical—through the mix of testimonial sincerity and scholarly rigor that I felt had been missing for over 20 years.

My scholarship and pedagogy have always drawn liberally from the work of Michel Foucault, who argued for studying, not prevailing trends, but the “discontinuity” or “rupture” in idea formations. One gift from Foucault to me was interdisciplinarity and contrarianism, as well as a fervent transnational and multilingual ethos. Breaking outside of patterns, I learned from him, was key to freeing people from the powerlessness of paradigms imposed on them by others. For this reason, when I delivered a speech at Stanford University on April 5 as part of my efforts to move children’s rights scholarship in a new direction, I made Foucauldian anaylsis the centerpiece of my talk.

The fruition of years of refining different perspectives on children’s rights came in that October conference, where experts in the fields of third-party reproduction, divorce law, and adoption—Alana Newman, Jennifer Lahl, Jennifer Roback-Morse, Claudia Corrigan D’Arcy, and Cathi Swett—delivered multidisciplinary feminist readings of children’s rights before a pavilion where my students’ 80 research exhibits were displayed.

We’ll Tell You How to Feel

The conference was consciously not structured as a rebuttal of gay parenting, and that made me very happy. For too long, an overemphasis on statistics and excessive pressure from the gay lobby had skewed scholarship on children. One of my biggest complaints coming out of the Mark Regnerus firestorm of 2012 was that the social sciences had been given free reign to dictate to children raised by same-sex couples how they were supposed to feel.

Oftentimes when I was interviewed or when I debated, people would tell me, “But, Mr. Lopez, all the social science indicates that children do just as well in same-sex households.” Citations of the American Pediatric Association or the American Medical Association typically ensued. As a humanities professor, I faced a conundrum: I was arguing not only against an individual who was telling me that I had no right to feel the way I actually did about being deprived of a father; I was also arguing against a technocratic, deeply anti-humanist philosophy that felt comfortable reducing the higher aims of life to statistics. And we all know what Mark Twain had to say about statistics.

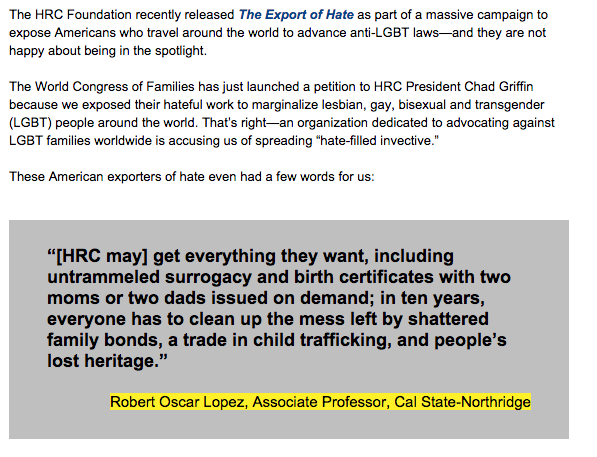

So all that was behind me and I was in an exhilarated mood by Monday, October 6, when I faced a crushing blow at work. I arrived at the office to discover that untold hundreds of people in my office had received an email overnight, which had actually been sent by the nation’s largest gay rights organization to more than a million people. Here is what the email said:

I saw, in an instant, a whole life of scholarship go up in smoke. Many of my students had gotten some version of this message by mid-morning; they were visibly furious that I had, in their minds, tricked them in some way. Did I have them spend so many hours of research on those exhibits just to advance an “anti-gay” agenda? They asked me directly, and I had to explain what was going on in shaken class discussions where all the focus on our collective accomplishment as humanities scholars faded before the exact thing I had tried to avoid: the reductive, mind-numbing, platitudinous debate about “pro-gay” versus “anti-gay” moral attitudes.

Ty Cobb’s email exemplifies everything that is wrong with present-day scholarship. Whole careers can be reduced, through selective quoting and willful misrepresentations, to sound bytes that destroy people’s careers. The scholar himself, in my shoes, is powerless, lacking a megaphone loud enough or the funds to refute point by point all the lies and deceptions in campaigns of character assassination.

Let’s Get Some Facts Straight

I have never been a member of the World Congress of Families, and had nothing to do with a petition forwarded to Griffin on that group’s behalf. I am classified as an “exporter of hate” by the Human Rights Campaign (HRC) because I critique an array of parenting arrangements that happen to include same-sex parenting, I speak foreign languages, and I travel outside the United States. But notice how this email implies that the quote attributed to me was delivered somehow in conjunction with my travel overseas, and that this travel was connected in some way to my job.

I have traveled to Great Britain, France, Italy, and Belgium as part of my research and activism on children’s rights. That is how I built the advisory boards for my institute and made them international in scope. The other countries listed in Cobb’s email—Russia, Uganda, etc.—are places whose laws I have repudiated publicly and which I have never visited.

The quote attributed to me in Cobb’s email came from this blog post. If you read through the post and then see the quote, it will become immediately obvious that the quote is not anti-gay and I am not anti-gay. Most of the article was about my struggles as a queer soldier serving in the military during the debate about “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell,” my concern for the safety of gay men with the high rate of military rapes, and my conviction that we need more thorough debate and discussionabout the implications of new family structures for children. It is clear in that post that I want to frame the discussion not as a gay issue but rather as a children’s issue, and that I wish to criticize gay and straight people equally for offenses against children’s rights.

But in a paragraph, with a sound bite, and an email blast, a scholar’s world can come crashing down. My wife went into labor that afternoon as I stood before 30 of my students struggling to explain to them why they just found out their professor was high on a gay rights organization’s enemy list.

As I rushed to the hospital and tried to put this out of my mind, for the sake of my newborn son, I felt the four corners of the world closing in on me. There seemed no way out of an intellectual trap. Cobb is willing to eradicate the particulars of genre and the mise-en-scène of quotes taken out of context. He is also utterly comfortable engaging in blatant deception, making it seem as though I stated that quote in a country like Uganda at an event organized by the World Congress of Families. The HRC profile on me tells readers that I delivered speeches in Minnesota and France, but then quotes obscure blog posts I wrote as a kind of brainstorming. They refuse to show my actual words from the statements in either place, for readers would see that my tone was temperate and cautious about balancing gay rights with the rights of children.

The LGBT Lobby Hates Intellectual Trust-Busting

They are targeting me because I am a scholar, a translator, a writer, a speaker, a professor. People who travel to other countries, speak to foreigners in other languages, and read many kinds of literature endanger their monopoly on American discourse. They need platitudes to paper over people’s doubts. They need silence for their demands to go unchallenged. As I elaborated in a piece for American Thinker, this means, effectively, that scholarship itself threatens them.

Which brings me to my point. Under these conditions, research will die soon. Maybe it is already dead. Scholars cannot forge new ideas if they are punished for writing too much, publishing too much, considering too many ideas. There is no way for one lone scholar to prevail against full-time investigators paid by a massive lobbying organization to comb over that scholar’s work in search of embarrassing quotes. If every sentence must be written with safeguards against misquoting and interpretive abuse, then every scholarly study will sound the same, argue the some points, and support the same conclusion. That is how the field of sociology arrived at its now famous “consensus” about same-sex parenting, which Loren Marks deconstructed in 2012.

No comments:

Post a Comment